I recently wrote a post for the MIT Press blog about the connections we can tease out between US history of computing and British history of computing. The two aren’t so similar as they may seem, and the things we can learn about the US from the British context might surprise you.

From the MIT Press Blog:

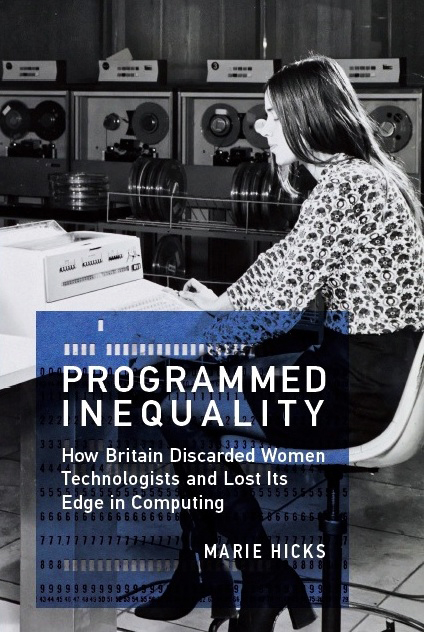

Margot Lee Shetterly, the author of Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race has praised Programmed Inequality, saying, “Marie Hicks’s well-researched look into Britain’s computer industry, and its critical dependence on the work of female computer programmers, is a welcome addition to our body of knowledge of women’s historical employment in science and technology. Hicks confidently shows that the professional mobility of women in computing supports the success of the industry as a whole, an important lesson for scholars and policymakers seeking ways to improve inclusion in STEM fields.”

In this post, Marie Hicks explains why, even today, possessing technical skill is not enough to ensure that women will rise to the top in science and technology fields, how the disappearance of women from the field had grave macroeconomic consequences for Britain, and why the United States risks repeating those errors in the twenty-first century.

***

Margot Shetterly’s book Hidden Figures is a masterpiece of history of technology. It shows how the struggles of black women impact technological advance in ways that we still don’t pay enough attention to.

The film based on that book takes things in a more feel-good direction, telling audiences an inspirational story about the triumphs of NASA’s black women mathematicians or human “computers.” At the end of the movie, the United States is coming from behind in the Space Race, and though Dorothy Vaughan, Katherine Johnson, and Mary Jackson are all still being denied their civil rights in the wider world, they emerge as heroes, and as respected movers and shakers at work. All’s well that ends well, the film seems to say.

Despite not allowing black citizens to reach their full potential in any sphere, the US still manages to “win” the Space Race by putting a man on the moon. The book shows how critical the submerged, highly skilled labor of these women was—why it was instrumental to US success—and finds a place for them in the canon of technological greats. A skeptical reader, however, might be inclined to question whether the contributions of these women really did make a “make or break” difference. Was there really such a strong connection between their work and the US winning the Space Race? Is there another case in which we can see the flip side of this scenario, where a nation has failed on the global stage because it did not harness the power of women’s technical skill?

As it turns out, there is a very good example of exactly this kind of failure. It’s the subject of my recent book, Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Their Edge in Computing. The twentieth century history of our closest historical cousin allows us to see very clearly what would’ve happened if NASA and the United States had done anything less than they did to leverage the skills of black (and white) women workers… Read the rest on the MIT Press website.

My book,

My book,