Digital humanities, tacit knowledge, and (re)making the world in whose image?

This year, I helped set up a digital humanities speaker series for our department, titled Goals and Boundaries in the Digital Humanities. The series will bring in speakers from inside and outside IIT to discuss the current state of the art in digital humanities and explore disciplinary issues associated with the field. The speakers come from many backgrounds–different academic humanities disciplines, library and archive work, computer science, museum studies, design, and public history.

As I was working on it, I ran into some articles that seemed especially apropos given that our speaker series is part of a larger effort to define what we should be aiming for as we try to create a digital humanities program within the department.

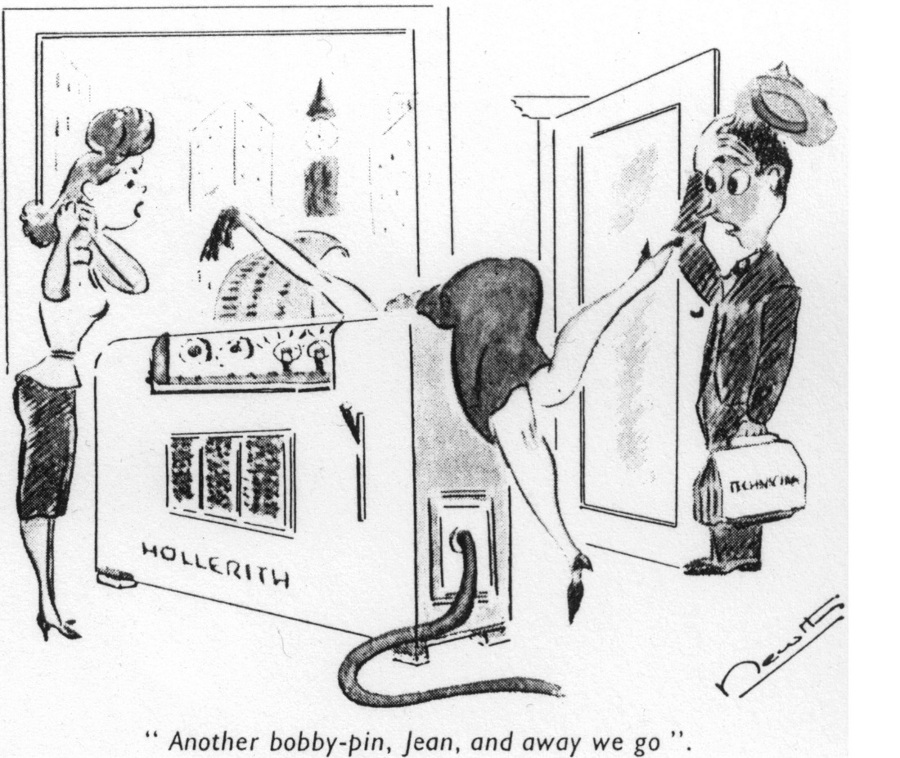

The first looks at the implications of tacit knowledge and the “commonsense” divisions thrown up between being, thinking, doing, and discourse. It struck an especial chord with me because of what I work on–in addition to the implications of race and privilege the author points out, there is a subtly gendered order at work here as well. Framing the debate as being between those who do (hackers) and those who can only sit on the sidelines and talk (yackers) implicitly leverages a long history of gendered categories–from those surrounding masculine professional expertise, to those enabling and privileging amateur tinkering.

The second article is a response to the first that hits on many of my concerns, and additionally points out how queer and postmodern analysis may in fact be deprecated by the hack ideal. I like how this piece encourages us to think about the hidden issues at work in the creation of canonical knowledge in the digital humanities: what exactly do we know as we’re trying to create new knowledge? And how does this old knowledge in fact predetermine much of the new?

I’m sure we’ll discuss these issues (and more) as we proceed through our seminar series. Anyone at IIT (and other local universities) is welcome to attend. The first meeting is on September 20th, in Siegel Hall, room 218 conference room.