Pieces of history

(Scroll to end of post for 6 minute audio documentary)

In the middle of the woods in Durham, North Carolina there is an abandoned dinosaur. It remains one of the greatest curiosities I’ve stumbled on in my life, and it got me thinking about how we can tell history through objects.

So here goes: at over 100 feet long and 30 feet tall, the Durham dinosaur is probably the biggest thing I’ve ever walked by without seeing. It was part of an educational “dinosaur park” that was attached to the Durham Museum of Life and Science, but in the 1990s the rest of the park was severely damaged by Hurricane Fran. As a result the exhibit was closed and the remaining sculptures fell into disrepair as the forest grew to engulf them. The brontosaurus remained, but it became largely invisible behind the trees and dense underbrush, despite its great size.

The Museum moved to a better building across the street, and on to other exhibits with a  different focus. In fact, the museum had steadily expanded since the original dinosaur park was built in 1964 by a determined and energetic young man who started as a volunteer and then served as curator and director for many years.

different focus. In fact, the museum had steadily expanded since the original dinosaur park was built in 1964 by a determined and energetic young man who started as a volunteer and then served as curator and director for many years.

Richard Wescott, born in England in 1924, joined the British Navy at 17 and served as a radio operator during World War II. While in the service, he met a young woman who was a lieutenant in the US Army’s Nursing Corps. He married her, and came back to the U.S. as a “war bride.” Wescott and his wife settled in Durham, in a neighborhood that was itself largely a creation of the post-war boom years. The area was touched by World War II in other ways: only a few years earlier German prisoners of war had been kept in a camp in a nearby town.

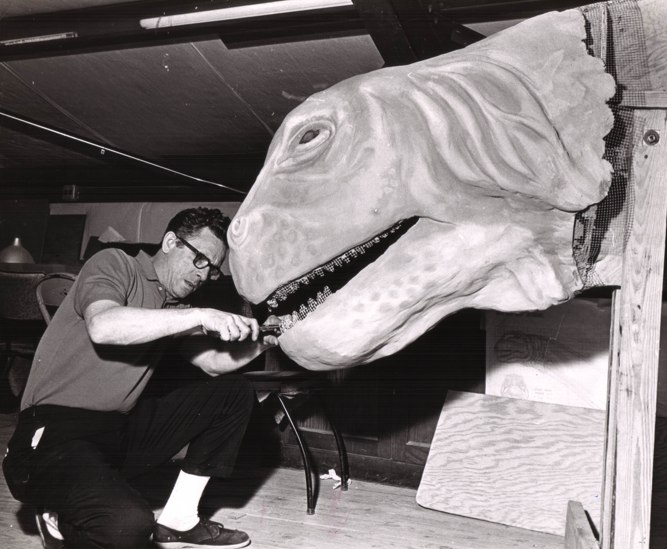

When Wescott began working at the Museum, it was known as the “Children’s Museum.” It had only begun in 1946. Early memorable exhibits were said to include a stuffed wallaby and a 2-headed calf. With Westcott’s hands-on intervention, the museum grew from a small-town curiosity to a regional attraction–the jewel in its collection being the outdoor dinosaur park that Wescott planned and spearheaded, going so far as to design and sculpt the figures himself. In 1964, he completed the massive brontosaurus, the  centerpiece of the park. In this picture, you can see Wescott working on its teeth, which he carefully sculpted out of chicken wire before covering them with fiberglass and paint. Unlike roadside dinosaur parks, the life-size models in the museum’s park were meticulously accurate, reflecting the best paleontological knowledge available at the time. In addition, they were naturalistic–and artistic–in ways that helped visitors easily imagine, on humid North Carolinian summer days, how these animals had once moved across the same earth that we now occupy. When the dinosaur park opened in 1970, it had close to a dozen sculptures, and more were added in the next few years. None remain except as wreckage hidden in the woods today. Except, that is, for the Brontosaurus.

centerpiece of the park. In this picture, you can see Wescott working on its teeth, which he carefully sculpted out of chicken wire before covering them with fiberglass and paint. Unlike roadside dinosaur parks, the life-size models in the museum’s park were meticulously accurate, reflecting the best paleontological knowledge available at the time. In addition, they were naturalistic–and artistic–in ways that helped visitors easily imagine, on humid North Carolinian summer days, how these animals had once moved across the same earth that we now occupy. When the dinosaur park opened in 1970, it had close to a dozen sculptures, and more were added in the next few years. None remain except as wreckage hidden in the woods today. Except, that is, for the Brontosaurus.

Wescott and his family moved on to Georgia, where he headed another museum.  After the park closed in the 1990s, locals in the know still delighted in catching a glimpse, or a snapshot, of the old dinosaur when winter thinned the trees enough for it to be seen. It became a quiet local landmark, but it also steadily fell into disrepair. Its underside was clawed open and its interior became a home to raccoons–and at one point, a homeless person.

After the park closed in the 1990s, locals in the know still delighted in catching a glimpse, or a snapshot, of the old dinosaur when winter thinned the trees enough for it to be seen. It became a quiet local landmark, but it also steadily fell into disrepair. Its underside was clawed open and its interior became a home to raccoons–and at one point, a homeless person.

Then somebody cut off its head. Using a chainsaw, the vandals ripped the concrete and fiberglass skin off the neck and face, and then carted it away in a pickup truck, dumping it in the woods near a local high school. Though the museum knew the identities of the high-school-age vandals they kept it secret–for fear the community would try to do to them what they had done to the dinosaur. The bronto’s body still stood–a huge steel I-beam jutting out where the neck and head had been. With the enormous steel infrastructure of the dinosaur now exposed, it became clear how this sculpture had survived so well, for so long. It seemed to mark the end of an era. Standing headless, the care and memories embedded in the brontosaurus seemed to have evaporated. In their place had been left a surly reminder of antisocial acting out.

As it turned out, this was perhaps the best thing that could have happened to the old dinosaur. The community rallied around it, demanding that it be fixed and accorded the respect of a landmark, rather than being treated like a forgotten relic. It helped that the Museum was opening a new dinosaur park around the same time: dismantling the old dino would have torpedoed their publicity for the new exhibit given the enormous community pressure to fix it. The community raised $20,000 and the Museum hired an artist who creates large outdoor sculpture to not only repair the head and neck, but close up other tears that had developed, particularly the gutted belly area.

After that, improvements and beautification to the land around the dinosaur continued, rescuing it from the overgrowth that had obscured it. During a celebration of the dino’s  re-capitation, goats were brought in to eat away the underbrush, to the delight of children in attendance. (The photos above show the dinosaur after this clearing work had been completed.) Shortly after that, the trail on which it stands was renamed for the bronto’s creator, a tacit promise to the community that the dinosaur would continue to remain a Durham landmark.

re-capitation, goats were brought in to eat away the underbrush, to the delight of children in attendance. (The photos above show the dinosaur after this clearing work had been completed.) Shortly after that, the trail on which it stands was renamed for the bronto’s creator, a tacit promise to the community that the dinosaur would continue to remain a Durham landmark.

Throughout my relationship with the dinosaur I’ve been struck by how much history you can tell through a single object; how objects represent so much labor and activity, as well as the social and political relationships that create that labor and activity. (My colleagues in media archaeology already know this well.) The Durham dinosaur is an object that embodies and represents multiple chapters in American history: the postwar migration of Europeans to the U.S.; the rise of the “New South;” the development of different ideas about childhood, parenting, and education in the mid-to-late 20th century; and the ever-changing nature of scientific knowledge (the field of paleontology has repeatedly struggled to define what–or if–the brontosaurus was).

Perhaps even more important, however, is how an object helps hook us into the realities of the past by embodying a particular sense of time. The feelings one gets while interacting with a monumental sculpture older than oneself bridge the emotional distance between the present and past, creating a resonance with the history that delivered it. People rarely remember things: they remember how they feel about those things. This is usually what makes the difference between learning something or not, and between knowing or forgetting. This is what saves history from the void into which all our yesterdays eventually disappear.

A few years after I originally wrote this post I created a short audio documentary about the Durham dinosaur while taking a class at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University–many thanks to Aaron Smithers who taught the course. I was lucky enough to be able to interview Dusty Wescott (the son of Richard Wescott), the folks involved in repairing the dinosaur (especially “Save the Bronto” campaign leader Nancy Rizzo and sculptor Tripp Jarvis), and other members of the community. You can listen to a version of it here (6 minutes). Music credits: “The Engagement,” by Silent Partner, “Long Note Four,” by Kevin MacLeod, “Dog Park,” by Silent Partner, and “Succotash” by Silent Partner, from the YouTube rights free music collection.

Thank you for this wonderful article about such a wondrous piece of history in Durham, NC, where I lived for a while. Am so pleased to know that others share my delight in the preservation of cultural oddities… I am especially pleased to learn that Aaron Smithers was part of the genesis of the documentary you made on this piece… he was integral in adding a crown jewel to my book of historic photos, South Carolina Blues – and I think he is a cultural treasure! I will visit Bronto Trail the next time I come back up to Durham. Thank you, Marie. You are fantastic!

Thank you for your kind words, Clair! And yes, Aaron is terrific and it was a true pleasure to be taught by him. Say hi to the Bronto for me the next time you are in town!

The dinosaur trail was Dad’s gift to the museum.. He took pride in the fact that it was as authentic as his research could make it. All who found joy in it made him smile. What remains to give joy makes us smile for him. He had a job that led to these creative endeavors. The lasting interest is his legacy. That makes me smile………vwp

Thanks so much, Vicky! Your Dad’s work is amazing and inspiring–perhaps my favorite piece of Durham history 🙂

I remember well your very talented father — an exceptional individual in every respect. Among other things, of course, he contributed mightily to the establishment of the museum as an institution about which all citizens of Durham (and N.C.) can be justifiably proud. I know too, many of the NASA-related items simply would not have been acquired were it not for your father.

Dick Wescott was a remarkable and most talented individual — a most personable visionary. FYI — the steel superstructure of the dinosaur was fabricated by my father’s business Miller Mfg. Company that was located in Durham. Their main business was the fabrication and installation of steel dump truck bodies. The business was sold some years ago and is no longer in operation. P.S. I very much enjoyed your very fine article.

What a wonderful article. That dinosaur was a fixture of my youth. My grandparents took me to The Children’s Museum regularly. Great memories! Thank you for this history!

My children and I love this dinosaur..we named him Petey….we have fond memories of seeing him through the years!!! Nostalgic!!